Copyright © Stephen E. Jones[1]

This is part #27, "Other marks and images: burns," of my series, "The evidence is overwhelming that the Turin Shroud is Jesus' burial sheet!" For more information about this series, see the "Main index #1" and "Other marks and images #26." Emphases are mine unless otherwise indicated. Again see also, "The Shroud of Turin: 2.6. The other marks (1): Burns and water stains."

[Main index #1] [Previous: Other marks and images #26] [Next: Water stains #28]

- Other marks and images #26

- Burns #27

Note: This post will need to be updated in the light of Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito's water stain findings in part #28.

Introduction The most obvious[2] and prominent[3] marks on the  Shroud are those resulting from a fire in AD 1532 (see below).

Shroud are those resulting from a fire in AD 1532 (see below).

[Right (enlarge): Burns marks and patches on the frontal half of the Shroud resulting from the 1532 fire (outlined in green)[4]. The body image appears prominent in this photo but that is because it is enhanced by photography[5]. Seen directly it is very faint (see "Faint #11").]

1532 fire On the night of 4 December 1532 a fire broke broke out in the Sainte-Chapelle, Chambéry, France[6] (see below), where the Shroud had been kept since 1502[7]. The Shroud was folded in 48 layers[8] inside a wooden casket overlaid with silver[9]

[Left (enlarge): The restored Sainte-Chapelle, Chambéry, as it is today[10], after it was all but destroyed by a fire in 1532.]

that had been donated in 1509 by a former Duchess of Savoy, Margaret of Austria (1480–1530)[11]. The casket was in a cavity in the wall above the high altar behind an iron grille, secured by four locks each with a different

[Right (enlarge): The cavity in a wall of the Sainte-Chapelle, Chambéry[12], from where the Shroud was rescued in the 1532 fire.]

key and keyholder[13]. One of the keys was held by Canon Philip Lambert, who was present[14] but the other keyholders could not be located in time[15]. A local blacksmith, Guglielmo Pussod[16], was summonsed who, at great personal risk from falling burning roof timbers, prised opened the grille[17], and with the help of Canon Lambert, two of his clergy and the Duke's butler, carried the Shroud in its burning casket to safety[18].

Molten silver burned Shroud So hot was the fire that the casket's silver overlay had melted (at the melting point of silver ~960°C = ~1762°F)[19] and burned through a corner of the casket[20]. A drop of molten silver fell onto a corner of the folded Shroud[21] and then burned through all

[Left (enlarge)[22]: Burn marks on the back image. The left-most mark was `ground-zero' where the drop of molten silver first impacted the folded Shroud (see plan below). It is also `ground-zero' of the water poured into the burned hole in the casket (see future "Water stains #28). Yet note that none of the hundreds of scourge mark images, even those closest to the molten silver, melted, cracked or `ran' in the heat and steam (see close-up below), further proving that the Shroud image is not comprised of paint, pigment, dye or powder (see below).]

48 folds[23]. The Shroud itself did not catch fire due to lack of oxygen in the casket[24] and also water poured onto the burning casket and through its burned hole onto the Shroud[25]. Inside the casket the water would have become steam when it touched the molten silver[26].

Casket opened When the casket was opened[27] and the still-folded cloth was lifted out and laid out full-length[28], in the nearby ducal castle[29], it was found that the Shroud had been  badly damaged in a repeating pattern of symmetrical lozenge or diamond shaped burn marks[30].

badly damaged in a repeating pattern of symmetrical lozenge or diamond shaped burn marks[30].

[Right (enlarge): "Plan of the damage caused by the 1532 fire, showing how the Shroud was folded into 48 folds at the time of this incident."[31].]

But miraculously[32] (literally! - see below) the burns paralleled the all-important body image[33] and only the edges of the shoulders and upper arms were lost[34].

Natural experiment The 1532 fire and its extinguishment by water was a "natural experiment"[35] which provided further evidence that the Shroud man's image was not painted [see "No paint, etc. #15"] with any medieval or earlier paint, pigment, dye or powder[36]. That is because if any coloured material had been added to the cloth to produce the image, it would have visibly changed[37] in the intense heat inside the casket, calculated to have been between 200°C to 300°C before the Shroud was doused with water[38]. But there is no such

[Left (enlarge)[39]: Close-up of the above `ground-zero' burn. There is no change to the scourging images closest to the molten silver, even though the blood (top) has been burned[40]. The lack of scourge marks at the burn's upper edge is because it was the gap between the body and arms (see ShroudScope), but lower down the scourge marks on the shoulder blades are unchanged under the burn!]

change[41]. Not even in those parts of the image closest to the molten silver at ~960°C[42] (see above). Nor did the image run or migrate through the water stains[43] (see next part #28 "Water stains").

Shroud's survival a miracle To those who were present when the twelve by four folded[44], 442.5 x 113.7 cms Shroud (see below), i.e. 442.5/12 = ~36.9 x 113.7/4 = ~28.4 cm, or 14.5 in x ~11.2 in, fire damaged Shroud bundle was lifted out of its ruined casket and was opened out full-length, and saw that the Shroud image was untouched by the fire except for the edge of the shoulders and upper arms, the Shroud's survival through the 1532 fire was a miracle[45]. But some modern Christian writers hedge their bets on this. For example, to Ian Wilson in 1979, the Shroud's survival was only "seemingly miraculously":

"On the night of December 4, 1532, fire broke out in the Sainte Chapelle, Chambéry, where the Shroud was then kept. Flames spread quickly through the chapel, engulfing rich furnishings and hangings in their path. A beautiful stained-glass window of the Shroud, completed only ten years earlier, melted in the heat, and the cloth itself was only saved by the quick intervention of one of the duke of Savoy's counselors, Philip Lambert, and two Franciscan priests. Together they managed to carry the already burning casket out of the building. But they were too late to prevent a drop of molten silver falling onto the linen inside. This set fire to one edge, scorching all forty-eight folds before the fire could be doused with water. When the reliquary was opened up, the Shroud presented a sorry picture of holes, scorch marks, and stains left by the water. Yet, seemingly miraculously, the image itself had scarcely been touched"[46]But by 2010, to Wilson it was only "most eerily" and "some extraordinary quirk of fate"[47]:

"But what truly arrested those present was the way that the fire damage the Shroud had sustained had, most eerily, missed the all-important image"To Mark Oxley in 2010 the Shroud's survival of the 1532 fire was only, "Almost as if by a miracle" (whatever that means):

"Yet by some extraordinary quirk of fate, the all-important imprint had scarcely been touched."

"One night in December 1532 a fire broke out in the Sainte Chapelle, Chambéry, in south-eastern France, where the Shroud was then being kept. The flames rapidly consumed the furnishings in the church and a stained-glass window depicting the Shroud melted in the heat. The Shroud itself was saved by the quick thinking of one of the Duke of Savoy's counsellors, Philip Lambert, who, with the help of two Franciscan priests, retrieved the casket containing the Shroud and carried it out of the burning building. However a drop of molten silver fell on to the linen inside the casket, resulting in scorching of all forty-eight folds of the Shroud. This was then doused with water, which resulted in further stains. Almost as if by a miracle the image itself was scarcely touched"[48].However, Rex Morgan in 1980 affirmed "the miraculous survival of the Shroud" through the 1532 fire:

"On 4th December 1532 there occurred an event, the consequences of which can be studied on the Shroud itself today. A fire broke out in the sacristy of the Holy Chapel at Chambéry. Historical accounts tell us that within a few minutes the whole building was alight and the silver casket in which the Shroud was kept had started to melt. Two Franciscan priests and a blacksmith managed to get into the building and rescue the relic but not before the molten silver had burned through the corner of the cloth and its forty-eight folds. These burn marks are the most apparent marks on the Shroud when one sees it in reality or on photographs today. What is interesting and entirely consistent with the miraculous survival of the Shroud is that the image of Christ was itself hardly affected by the fire at Chambéry ..."[49].I also affirm that the survival of the Shroud through the 1532 fire was a miracle, supernaturally controlled by Jesus, whose Shroud it is, and who is ruling over all (Mt 28:18; Acts 10:36; Rom 9:5; Eph 1:21-22; Php 2:9). Specifically I affirm that the survival of the Shroud, against all the odds, through the 1532 fire was what evangelical Christian philosopher Norman Geisler termed a "second class miracle":

"It may be that some things are so highly unusual and coincidental that, when viewed in connection with the moral or theological context in which they occurred, the label `miracle' is the most appropriate one for the happening. Let us call this kind of supernaturally guided event a second class miracle, that is, one whose natural process can be described scientifically (and perhaps even reduplicated by humanly controlled natural means) but whose end product in the total picture is best explained by invoking the supernatural"[50].Here are ten things which could have gone wrong, any one of which would have left no Shroud after 1532, but didn't:

- Fire was discovered too late. Sainte Chapelle, Chambéry was completely destroyed and the Shroud in it.

- Blacksmith was not available or unwilling to risk his life entering the burning chapel.

- Three other men not available or unwilling to risk their lives entering the burning chapel.

- Four men available and willing, but driven back by intense heat, which melted silver at ~960°C, so unable to rescue the Shroud.

- Burning roof timbers fell into chapel, killing all four men and destroying the Shroud.

- Blacksmith unable in intense heat to break open the red hot iron grille and rescue the Shroud.

- Four men unable to carry the too hot burning casket though the burning chapel.

- More molten silver burnt through a larger area of the casket top, fell onto the folded Cloth, let in more oxygen and incinerated the Shroud.

- Molten silver burned through the middle of the casket top and destroyed the image.

- Shroud was folded in a configuration such that the corner drop of molten silver did not miss the image.

But this is only part of a larger pattern of Divine preservation that has ensured the Shroud has survived, against the odds, down through the centuries, a "frail piece of linen" when "every edifice in which the Shroud was ... housed before the fifteenth century has long since vanished":

"For if the author's [Ian Wilson's] reconstruction is correct, the Shroud has survived first-century persecution of Christians, repeated Edessan floods, an Edessan earthquake, Byzantine iconoclasm, Moslem invasion, crusader looting ... not to mention the burning incident that caused the triple holes, the 1532 fire, and a serious arson attempt made in 1972. It is ironic that every edifice in which the Shroud was supposedly housed before the fifteenth century has long since vanished through the hazards of time, yet this frail piece of linen has come through almost unscathed"[51].

1534 repairs On 16 April 1534 the Shroud was carried in a procession led by Duke Charles III (1486-1553) and the Papal Legate, Cardinal Louis de Gorrevod (c.1473-1535), from the ducal castle to the convent of Chambéry's Poor Clare nuns[52]. There under the leadership of Abbess Louise de Vargin[53], the Shroud was laid full-length on a stiff Holland cloth backing[54], which was attached to a wooden frame[55], which in turn had been laid on a large table brought from the castle, upon which the Shroud had been lying[56]. Charred areas were removed from the Shroud and replaced by triangular white linen altar cloth patches[57] which were sewn to the Holland cloth backing[58]. Despite a constant stream of visitors arriving to see the Shroud[59], on 2 May the repairs were completed[60]. The Shroud was rolled around a wooden cylinder with a sheet of red silk, then covered in cloth of gold, and returned to the Savoy castle[61]. On 4 May 1534, the Shroud's traditional annual feast and exposition day[62], it was briefly displayed from Chambéry castle to reassure the public[63]. Abbess de Vargin wrote a report on the Shroud and its repair[64].

2002 restoration Following concerns that the remaining burnt areas  may be chemically reacting with the Shroud's linen[65], in 2002 under the leadership of ancient textiles conservator Mechthild Flury-Lemberg[66], the 1534 patches were removed[67], burnt particles vacuumed up[68], the old 1534 Holland cloth backing removed[69] and replaced by a new backing cloth[70]. In removing the 1534 Holland cloth backing, Flury-Lemberg became the first person to see the full underside of the Shroud in ~468 years[71]. She found no

may be chemically reacting with the Shroud's linen[65], in 2002 under the leadership of ancient textiles conservator Mechthild Flury-Lemberg[66], the 1534 patches were removed[67], burnt particles vacuumed up[68], the old 1534 Holland cloth backing removed[69] and replaced by a new backing cloth[70]. In removing the 1534 Holland cloth backing, Flury-Lemberg became the first person to see the full underside of the Shroud in ~468 years[71]. She found no

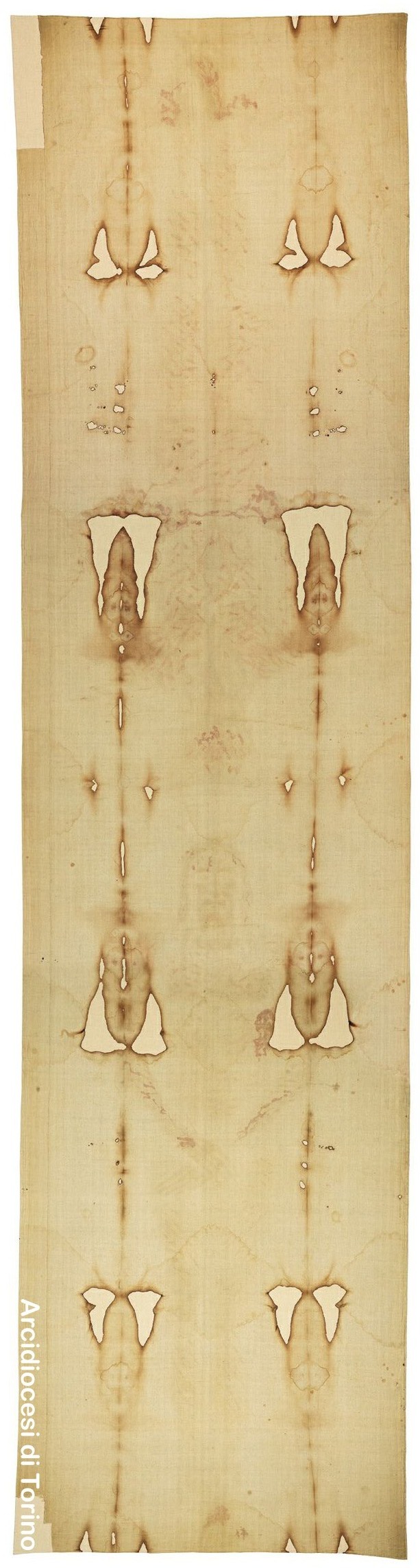

[Right (enlarge): The Shroud after the 2002 restoration[72].]

evidence of "invisible mending" as proposed by Benford and Marino's "invisible reweaving" theory[73] (see my "The 1260-1390 radiocarbon date of the Turin Shroud was the result of a computer hacking #1"). But Flury-Lemberg did discover that the stitching of the seam joining the sidestrip to the main body of the Shroud was most unusual[74], and which in her experience she had only seen in textiles found in the ruins of the Jewish fortress at Masada which was conquered by the Romans in AD 74 and never occupied since[75]! (See my "Sidestrip #5"). Flury-Lemberg also accurately measured the Shroud at 437 cm x 111 cm[76], later revised to 442.5 cm x 113.7 cm[77](~14 ft 6 in x 3 ft 9 in)[78].

Problem for the forgery theory (see previous three: #23, #24 and #25). This section was inadvertently omitted but will be completed in the update in the light of Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito's water stain findings in part #28.

Continued in the next part #28 of this series.

Notes

1. This post is copyright. I grant permission to quote from any part of this post (but not the whole post), provided it includes a reference citing my name, its subject heading, its date and a hyperlink back to this page. [return]

2. McNair, P., "The Shroud and History: fantasy, fake or fact?," in Jennings, P., ed., 1978, "Face to Face with the Turin Shroud ," Mayhew-McCrimmon: Great Wakering UK, p.22; Jumper, E.J., Adler, A.D., Jackson, J.P., Pellicori, S.F., Heller, J.H. & Druzik, J.R., in Lambert, J.B., ed., 1984, "A Comprehensive Examination of the Various Stains and Images on the Shroud of Turin,"Archaeological Chemistry III: ACS Advances in Chemistry, No. 205," American Chemical Society, Washington D.C., pp.447-476, 449; Hoare, R., 1999, "The Turin Shroud Is Genuine: The Irrefutable Evidence Updated," [1984], Souvenir Press: London, pp.18, 24; Ruffin, C.B., 1999, "The Shroud of Turin: The Most Up-To-Date Analysis of All the Facts Regarding the Church's Controversial Relic," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, p.10. [return]

4. Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002: Horizontal: Overlays: Burn Holes (1532 A.D.)" (rotated left 90°), Sindonology.org. [return]

5. Wilson, I., 1979, "The Shroud of Turin: The Burial Cloth of Jesus?," [1978], Image Books: New York NY, Revised edition, pp.21-22, 219; Borkan, M., 1995, "Ecce Homo?: Science and the Authenticity of the Turin Shroud," Vertices, Duke University, Vol. X, No. 2, Winter, pp.18-51, 32; Wilson, I., 2010, "The Shroud: The 2000-Year-Old Mystery Solved," Bantam Press: London, pp.7, 10. [return]

6. Morgan, R., 1980, "Perpetual Miracle: Secrets of the Holy Shroud of Turin by an Eye Witness," Runciman Press: Manly NSW, Australia, p.45; Wilson, 1979, p.24; Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1981, "Verdict on the Shroud: Evidence for the Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ," Servant Books: Ann Arbor MI, p.30; Crispino, D.C., 1982, "The Report of the Poor Clare Nuns: Chambéry, 1534," No. 2, March, pp.19-28, 19; Cruz, J.C., 1984, "Relics: The Shroud of Turin, the True Cross, the Blood of Januarius. ..: History, Mysticism, and the Catholic Church," Our Sunday Visitor: Huntington IN, p.49; Wilson, I., 1986, "The Evidence of the Shroud," Guild Publishing: London, p.2; Petrosillo, O. & Marinelli, E., 1996, "The Enigma of the Shroud: A Challenge to Science," Scerri, L.J., transl., Publishers Enterprises Group: Malta, p.162; Hoare, 1999, pp.18-19, 24; Iannone, J.C., 1998, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin: New Scientific Evidence," St Pauls: Staten Island NY, p.141; Guerrera, V., 2001, "The Shroud of Turin: A Case for Authenticity," TAN: Rockford IL, p.18; Cassanelli, A., 2002, "The Holy Shroud," Williams, B., transl., Gracewing: Leominster UK, p.14; Tribbe, F.C., 2006, "Portrait of Jesus: The Illustrated Story of the Shroud of Turin," Paragon House Publishers: St. Paul MN, Second edition, p.49; Oxley, M., 2010, "The Challenge of the Shroud: History, Science and the Shroud of Turin," AuthorHouse: Milton Keynes UK, pp.4, 76; Wilson, 2010, pp.14, 305. [return]

7. Iannone, 1998, pp.141-142; Oxley, 2010, p.76; Wilson, 2010, pp.249, 305. [return]

8. Hynek, R.W., 1951, "The True Likeness," [1946], Sheed & Ward: London, p.3; Humber, T., 1978, "The Sacred Shroud," [1974], Pocket Books: New York NY, p.105; Wilson, 1979, p.24; Morgan, 1980, p.45; Wilson, 1986, p.2; Wilson, 1998, p.65; Oxley, 2010, p.4. [return]

9. Morgan, 1980, p.45; Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.30; Wilson, 1986, p.2; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.162. [return]

10. "File:Sainte-Chapelle (Chambéry).jpg," Wikipedia, 7 May 2016. [return]

11. Ruffin, 1999, p.67. [return]

12. Moretto, G., 1999, "The Shroud: A Guide," Neame, A., transl., Paulist Press: Mahwah NJ, p.19. [return]

13. Wilson, 1986, p.2; Wilson, I., 1998, "The Blood and the Shroud: New Evidence that the World's Most Sacred Relic is Real," Simon & Schuster: New York NY, p.65. [return]

14. Crispino, 1982, p.19. [return]

15. Wilson, 1986, p.2; Wilson, 1998, p.65; Wilson, 2010, p.14. [return]

16. Humber, 1978, p.105; Wilson, 1998, pp.65, 289; Guerrera, 2001, p.18; Oxley, 2010, pp.77, 277; Wilson, 2010, p.253. [return]

17. Wilson, 1986, p.2; Ruffin, 1999, p.67; de Wesselow, T., 2012, "The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection," Viking: London, p.16; Wilson, 2010, p.14, 305. [return]

18. Hynek, 1951, p.11; Wilson, 1979, p.24; Morgan, 1980, p.45; Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.30; Cruz, 1984, p.49; Iannone, 1998, pp.141-142; Hoare, 1999, p.19; Ruffin, 1999, p.67; Guerrera, 2001, p.18; Oxley, 2010, p.4; Wilson, 2010, p.14. [return]

19. Heller, J.H. & Adler, A.D., 1981, "A Chemical Investigation of the Shroud of Turin," in Adler, A.D. & Crispino, D.C., ed., 2002, "The Orphaned Manuscript: A Gathering of Publications on the Shroud of Turin," Effatà Editrice: Cantalupa, Italy, pp.34-57, 35; Schwalbe, L.A. & Rogers, R.N., 1982, "Physics and Chemistry of the Shroud of Turin: Summary of the 1978 Investigation," Reprinted from Analytica Chimica Acta, Vol. 135, No. 1, 1982, pp.3-49, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co: Amsterdam, p.23; Cruz, 1984, p.49; Stevenson, K.E. & Habermas, G.R., 1990, "The Shroud and the Controversy," Thomas Nelson: Nashville TN, p.57; Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.176; Borkan, 1995, pp.32, 48; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.217; Iannone, 1998, p.3; Antonacci, M., 2000, "Resurrection of the Shroud: New Scientific, Medical, and Archeological Evidence," M. Evans & Co: New York NY, p.48; Smith, P.R., 1996, "A scientific appraisal of the Allen hypothesis for the formation of the image on the Shroud of Turin," Shroud News, No. 94, April, pp.10-14, 11; Hoare, 1999, p.19. [return]

20. Hoare, 1999, p.19; de Wesselow, 2012, p.16. [return]

21. Hynek, 1951, p.3; Humber, 1978, p.36; Iannone, 1998, p.3; Moretto, 1999, p.19; Oxley, 2010, p.4. [return]

22. Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002: Vertical," Sindonology.org. [return]

23. Humber, 1978, p.105; Cruz, 1984, p.49; Moretto, 1999, p.19; Oxley, 2010, p.4; de Wesselow, 2012, p.16. [return]

24. Borkan, 1995, p.38; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, pp.217-218. [return]

25. Cruz, 1984, p.49. [return]

26. Wilson, I., 1991, "Holy Faces, Secret Places: The Quest for Jesus' True Likeness," Doubleday: London, p.176; Wilson, 2010, p.93. [return]

27. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Oxley, 2010, p.77. [return]

28. Wilson, 1998, p.65; Oxley, 2010, p.78. [return]

29. Rinaldi, P.M., 1978, "The Man in the Shroud," [1972], Futura: London, Revised, p.20; Wilson, 1979, p.24. [return]

30. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Wilson, 1986, p.2; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.162; Wilson, I. & Schwortz, B., 2000, "The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence," Michael O'Mara Books: London, p.22; Oxley, 2010, p.78. [return]

31. Wilson, 1998, p.65. Wilson's photo has been rearranged to fit. [return]

32. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Morgan, 1980, p.45; Crispino, 1982, p.20; Wilson, 1998, p.65; Hoare, 1999, p.19; Oxley, 2010, p.4; Wilson, 2010, p.304. [return]

33. Morgan, 1980, p.45; Adler, A.D., 1996, "Updating Recent Studies on the Shroud of Turin," in Adler & Crispino, 2002, pp.81-86, 81; Ruffin, 1999, pp.11-12; Guerrera, 2001, p.18; Oxley, 2010, p.4. [return]

34. Hynek, 1951, p.3; Sullivan, B.M., 1973, "Reading the Shroud of Turin: How in fact was Jesus Christ laid in his tomb?," National Review, July 20, Reprinted March 24, 2005; Wilson, 1998, p.23. [return]

35. Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.30; Antonacci, 2000, pp.48-49, 73-74; Murphy, C., 1981, "Shreds of evidence: Science confronts the miraculous - the Shroud of Turin," Harper's, Vol. 263, November, pp.42-68, 64; Rogers, R.N., 2008, "A Chemist's Perspective on the Shroud of Turin," Lulu Press: Raleigh, NC, p.10. [return]

36. Murphy, 1981, p.55; Schwalbe & Rogers, 1982, p.24; Adler, A.D., 1999, "The Nature of the Body Images on the Shroud of Turin," in Adler & Crispino, 2002, pp.103-112, 105; Adler, A.D., 2000c, "Chemical and Physical Aspects of the Sindonic Images," in Adler & Crispino, 2002, pp.10-27, 16-17; Antonacci, 2000, p.48; Tribbe, 2006, p.127; Oxley, 2010, p.210. [return]

37. Borkan, 1995, pp.23-24; Antonacci, 2000, p.48; Tribbe, 2006, p.127; Rogers, 2008, p.10. [return]

38. Culliton, B.J., 1978, "The Mystery of the Shroud of Turin Challenges 20th-Century Science," Science, Vol. 201, 21 July, pp.235-239, 236. [return]

39. Latendresse, M., 2010, "Shroud Scope: Durante 2002: Horizontal," (rotated left 90°), Sindonology.org. [return]

40. Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.162. [return]

41. Culliton, 1978, p.236; Murphy, 1981, p.55; Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.67; Schwalbe & Rogers, 1982, p.24; Adler, 1999, p.105; Adler, 2000c, pp.16-17; Antonacci, 2000, p.48; Tribbe, 2006, p.127; Oxley, 2010, p.210. [return]

42. Murphy, 1981, pp.55-56; Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.67; Adler, 1999, p.105. [return]

43. Stevenson & Habermas, 1981, p.107; Antonacci, 2000, p.48; Oxley, 2010, p.210. [return]

44. Hynek, 1951, p.3; Hoare, 1999, p.19; Tribbe, 2006, p.11. [return]

45. Crispino, 1982, p.20; Scavone, D.C., 1995, "Philibert Pingon and the Shroud of Turin," Shroud News, No 87, February, pp.18-23,22. [return]

46. Wilson, 1979, p.24. [return]

47. Wilson, 2010, pp.254, 14. [return]

48. Oxley, 2010, p.4. [return]

49. Morgan, 1980, p.45. [return]

50. Geisler N.L., 1976, "Christian Apologetics," Baker: Grand Rapids MI, Ninth Printing, 1995, p.277. [return]

51. Wilson, 1979, p.251. [return]

52. McNair, 1978, p.22; Wilson, 1979, pp.24, 263; Morgan, 1980, p.45; Crispino, 1982, p.22; Wilson, I., 1996, "A Calendar of the Shroud for the years 1509-1694," BSTS Newsletter, No. 44, November/December; Crispino, D.C., 1998, "A Chronological Survey of Observations on the Shroud Textile," in Minor, M., Adler, A.D. & Piczek, I., eds., 2002, "The Shroud of Turin: Unraveling the Mystery: Proceedings of the 1998 Dallas Symposium," Alexander Books: Alexander NC, pp.279-286, 279; Iannone, 1998, pp.2-3; Wilson, 1998, p.289; Wilson & Schwortz, 2000, p.22; Guerrera, 2001, p.18; Oxley, 2010, p.78; Wilson, 2010, p.253. [return]

53. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Crispino, 1982, p.22; Oxley, 2010, pp.78, 277. [return]

54. Crispino, 1982, p.22; Wilson, 1996; Crispino, 1998. [return]

55. Crispino, 1982, p.22; Wilson, 1996; Crispino, 1998. [return]

56. Crispino, 1982, p.22; Wilson, 1996; Crispino, 1998. [return]

57. McNair, 1978, p.22; Wilson, 1979, p.24; Cruz, 1984, p.49; Guerrera, 2001, p.18; Wilson, 2010, pp.256, 304. [return]

58. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Petrosillo & Marinelli, 1996, p.162; Wilson, 1998, p.64; Wilson, 2010, p.304. [return]

59. Wilson, 1979, p.24. [return]

60. Wilson, 1979, pp.24, 262; Wilson, 1996; Guerrera, 2001, p.18. [return]

61. Wilson, 1979, p.24; Wilson, 1996; Wilson, 1998, pp.286, 290; Oxley, 2010, pp.78, 262; Wilson, 2010, p.256. [return]

62. Wilson, 1979, pp.218, 262; Morgan, 1980, p.45; Wilson, 1998, p.112; Ruffin, 1999, p.68; Whiting, B., 2006, "The Shroud Story," Harbour Publishing: Strathfield NSW, Australia, p.364; Oxley, 2010, pp.84; Wilson, 2010, pp.95; 253, 255-256, 264, 304; de Wesselow, 2012, p.16. [return]

63. Wilson, 1979, p.219; Tribbe, 2006, p.50. [return]

64. Crispino, 1982, pp.19-28. [return]

65. Adler, A.D., 1991, "Conservation and Preservation of the Shroud of Turin," in Adler & Crispino, 2002, pp.67-71, 69-70; Oxley, 2010, pp.263, 268; Wilson, 2010, p.286. [return]

66. Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Oxley, 2010, p.9; Wilson, 2010, pp.14, 70, 286, 310. [return]

67. Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Oxley, 2010, pp.9, 78, 263; Wilson, 2010, pp.15, 24, 286. [return]

68. Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Oxley, 2010, p.263; Wilson, 2010, p.15. [return]

69. Antonacci, 2000, p.187; Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Oxley, 2010, pp.244, 263; Wilson, 2010, pp.15, 24, 286. [return]

70. Antonacci, 2000, p.187; Oxley, 2010, p.244; Wilson, 2010, pp.15, 24, 310. [return]

71. Oxley, 2010, p.263; Wilson, 2010, pp.15, 72, plate 13b. [return]

72. "Image of Full 2002 Restored Shroud," High Resolution Imagery, Shroud University, 2014. [return]

73. Benford, M.S. & Marino, J.G., 2008, "Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin shroud," Chemistry Today, Vol 26, No. 4, July-August, pp.4-12; Oxley, 2010, p.229. [return]

74. Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Wilson, 2010, p.72. [return]

75. Tribbe, 2006, p.146; Wilson, 2010, pp.15, 72-74. [return]

76. Wilson, I., 2000, "`The Turin Shroud - past, present and future', Turin, 2-5 March, 2000 - probably the best-ever Shroud Symposium," British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, No. 51, June. [return]

77. Wilson, 2010, pp.311, 315. [return]

78. Wilson, 2010, p.71. [return]

Posted 20 January 2018. Updated 28 February 2023.